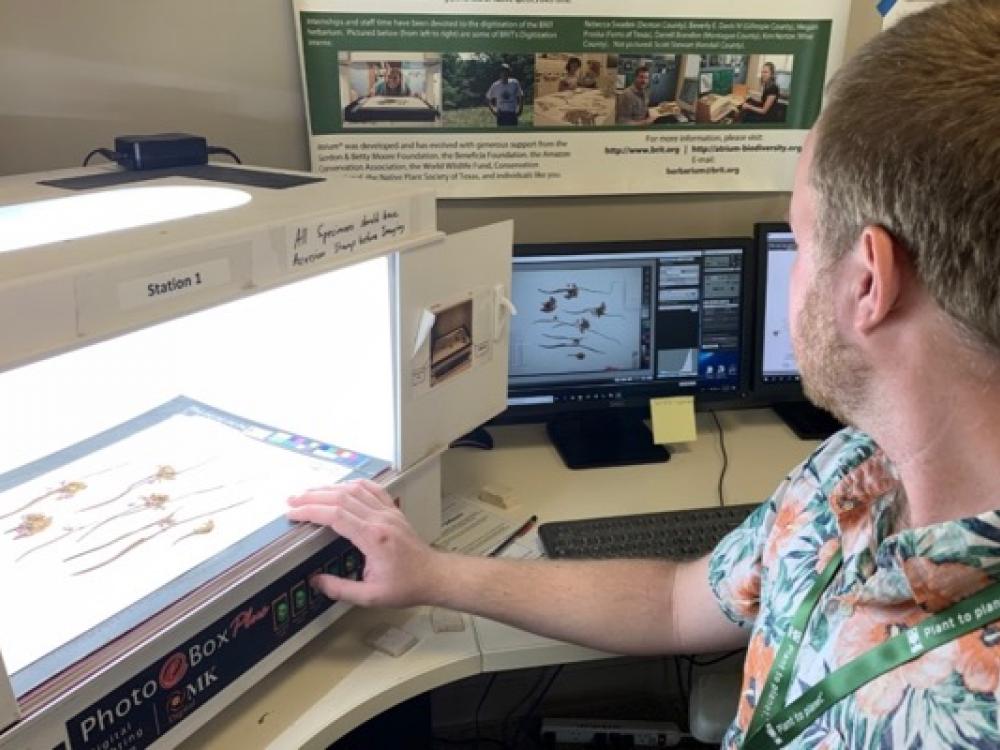

Joe Lippert captures digital images of plant specimens at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas with state-of-the-art Canon cameras. Photos courtesy of BRIT.

Aug. 21, 2019

Fort Worth’s art museums are legendary but did you know the city’s Cultural District is also home to a world class plant collection?

The Botanical Research Institute of Texas is located next door to the Fort Worth Botanic Garden and down the street from the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Outside, BRIT's state-of-the-art green campus includes a restored prairie, a living roof and rainwater gardens. Inside, an extensive database, library, publishing house and vaults filled with botanical treasures that are precious, historic, exotic and one of a kind are overseen by researchers who regularly field global queries.

The BRIT campus features a restored prairie and native plant demonstration gardens. Courtesy of BRIT.

PLANT MANAGER

Entirely serious science about plants, BRIT features at its core the Philecology Herbarium, one of the top 10 in the country, housing 1.5 million plant specimens, from common to extinct. The oldest date to 1791 Mexico.

Herbarium manager Tiana Rehman leafs through BRIT's plant specimen collection. Courtesy of BRIT.

Herbarium manager Tiana Rehman leafs through BRIT's plant specimen collection. Courtesy of BRIT.

Someone has to keep track of all those dried plant samples and that person is herbarium manager and botanist Tiana Rehman, a quick to smile petite dark-haired woman with inquisitive eyes that miss nothing. In her position since 2009, she facilitates the care, usage, and growth of the plant collection and its interpretation for the public.

Rehman is joyful in her position at BRIT, an enterprise dedicated to scientifically exploring the world’s flora. BRIT is big enterprise. Our planet is more accurately a plant-et. Animal, human, and insect life is minuscule compared to its rampant and abundant flora.

Herbarium holdings include vascular plants, including a seed, nut and mast (aka tree seed) collection and wood specimens. But there are also lichens, fungi, algae, slime molds, bryophytes such as mosses, even slides of microscopic pollen.

DRIED BITS OF HISTORY

BRIT was formed in 1987 to house the Lloyd H. Shinners Collection in Systematic Botany begun at Southern Methodist University. In 1997, the Vanderbilt University Herbarium, with its emphasis on threatened and endangered plants of southeast U.S., was donated to BRIT. The R. Dale Thomas Plant Collection from University of Louisiana at Monroe arrived ten years later. The herbarium has provided a secure location to house many orphaned collections.

Solidago californica, collected in Kiamath County, Oregon, in 1931. Courtesy of BRIT.

Solidago californica, collected in Kiamath County, Oregon, in 1931. Courtesy of BRIT.

Rehman spreads out large fat binders onto a table in a small laboratory. She opens the cover of one and a rush of aromas — herbaceous, acrid, spicy, astringent, musty — emerges from transparent sleeves filled with leaves and stems.

Flipping through the binders, we take a rollicking tour of multiple continents spanning many hundreds of years. A tropical plant from South America that looks menacing. Delicate forest groundcovers from the Rocky Mountains with teeny flowers. Unusual Mexican herbs.

Adiantum tenerum, collected in Florida. Courtesy of BRIT.

Adiantum tenerum, collected in Florida. Courtesy of BRIT.

Rehman radiates pride at her bounty of dried flora. Some plants related to each other are grouped, yet show the barest of visible variations to the leaves, stems and mast. A collection of plant specimens dating back a few centuries evokes wistful musings at the sad fate some of them faced.

“These are botanist forms of evidence, our plant history books,” says Rehman.

But this brightly lit, hyper-clean room crammed with flat drawers, cabinets and shelves is just a small portion. Rehman leads me into a dimly lit basement area with a sprawling warren of grey cabinets. Its crisp, dry air chills me to the bone.

BRIT's herbarium houses 1.5 million plant specimens dating back to 1791 Mexico. Courtesy of BRIT.

BRIT's herbarium houses 1.5 million plant specimens dating back to 1791 Mexico. Courtesy of BRIT.

Every drawer here has a story, and each plant is a character in that story. What possible solutions to modern problems lie in these plants?

“Researchers here used to say the cure for cancers could be found in our cabinets,” says Rehman.

That is no longer true. While the issue of drug discovery is much more complex, these specimens provide essential information for those engaged in that pursuit. Researchers can now discover these specimens online in BRIT’s online database.

DIGITAL AGE

For most of 2015, BRIT staff and interns inventoried herbarium contents, using open-source software developed in-house, with the help of 136 volunteers. In a process that continues today under Joe Lippert’s coordination, plant specimens are imaged at high resolution with highly technical Canon cameras.

The profuse data with each specimen — plant collection date and place, reason collected and by whom, and the research specimens were used for — was painstakingly entered into a database. A big challenge was converting the locality data to GPS.

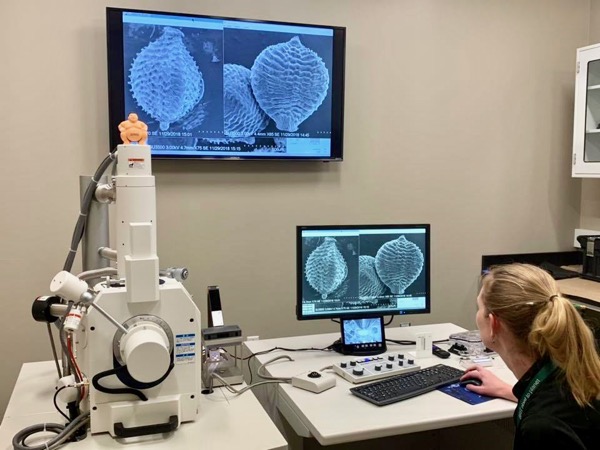

BRIT conservation biologist Kim Taylor tests a new scanning electron microscope. Courtesy of BRIT.

BRIT conservation biologist Kim Taylor tests a new scanning electron microscope. Courtesy of BRIT.

“Digitizing these collections means everyone can examine,” says Rehman. “We can rely on a world’s worth of experts to identify these plants and explore their usage.”

Digitizing is especially vital due to export restrictions on plant materials. Study requests arrive from around the globe. Many are from research ethnobotanists looking into historical plant use, tapping into knowledge gleaned by traditional indigenous cultures.

Far more than a medicinal resource, meteorologists compare the BRIT plants to weather statistics for insight on the impact of changing climate patterns. Ecologists and biologists examine how bugs and animals utilized plants over time.

DNA TRAILS

With the recent opening of the George C. and Sue W. Sumner Molecular and Structural Laboratory at BRIT, herbarium specimens can be examined down to their DNA level, revealing even more secrets. An ultra high-tech operation, visitors can only watch through large windows as technicians encased in sterile white operate their gleaming instruments.

This new wave of knowledge is transforming plant systematics, or the biological classification of plants, and the understanding of how plants evolved.

A class hikes through BRIT's restored prairie. Courtesy of BRIT.

A class hikes through BRIT's restored prairie. Courtesy of BRIT.

“We always have to keep up with changing taxonomy and more,” says Rehman.

She is charmed by the name of a National Science Foundation grant focused on digitization that will enable such studies: “Digitizing ‘Endless Forms’: Facilitating Research on Imperiled Plants with Extreme Morphologies”

The Charles Darwin quote it references encapsulates the mission of BRIT’s herbarium. At the same time, it celebrates the grand drive of our plant-et to diversify and be abundant, to grow and give without expectation, to be fertile and create beauty for the sheer joy of it:

“There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

RELATED ARTICLES

Botanical Research Institute of Texas opens new LEED facility in Fort Worth

Horses 'make hay' at the Botanical Research Institute of Texas

BRIT launches mobile app for plant ID

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter.