An adult American alligator heads for the water at Anuahuac National Wildlife Refuge near Galveston. Photo by Michael Smith.

Jan. 10, 2023

Alligator sightings by residents near Lake Worth spawned a meeting last month between a neighborhood group, the City of Fort Worth staff, and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

The meeting was introduced by Fort Worth City Council District 7 Director, Sami Roop.

An informal group from the South Shores neighborhood fear that someone will be hurt or killed by a gator. The residents reported seeing more alligators on or near their lakefront property in the last couple of years.

Alligators have lived in the area since at least 1849, according to Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge manager Rob Denkhaus, who attended the meeting.

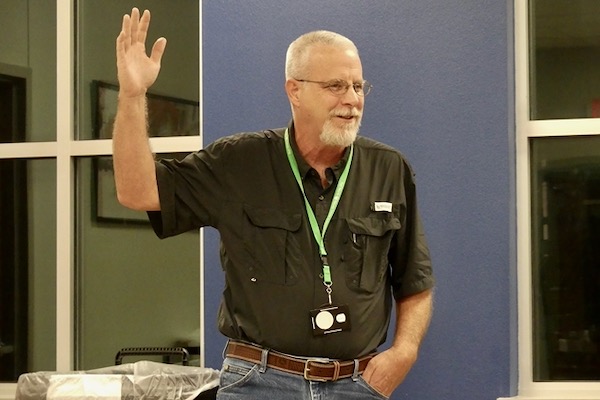

Fort Worth Nature Center manager Rob Denkhaus trys to quell residents' fears about local alligators. Photo by Michael Smith.

Fort Worth Nature Center manager Rob Denkhaus trys to quell residents' fears about local alligators. Photo by Michael Smith.

There has been a long history without serious trouble from the alligators, Denkhaus said.

Alligators are generally shy and mostly avoid interacting with humans.

But big ones are powerful and potentially dangerous. One fatality was reported in 2015 on the Texas coast when a man ignored warnings and jumped in for a nighttime swim with a large alligator. There don’t appear to be any other fatalities in Texas since at least the 1800s.

“99.9 percent of the time, people live responsibly and safely among alligators,” said Jonathan Warner, alligator program leader for TPWD, who also attended the meeting.

For example, in Huntsville State Park, humans and alligators share Lake Raven. Alligators hang out nearby as people enjoy the popular swimming hole.

“99.9 percent of the time, people live responsibly and safely among alligators,” said Jonathan Warner, alligator program leader for TPWD.

Nevertheless, some of the property owners at the meeting were skeptical about the creators’ harmlessness. One quoted safety guidance about not swimming when alligators are present and not allowing children to play at the water’s edge. She was unhappy to have the family’s activities limited by alligators.

“There’s not room for both of us,” she said.

Not everyone shared that view. In response to someone’s comment that “Nobody wants to live with alligators,” another resident said she disagreed. She spoke about her friends in Florida who have alligators on their property. She said they have even named the familiar ones.

HANDLING ENCOUNTERS

A young gator surveys the scene at Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge near Galveston. Photo by Michael Smith.

A young gator surveys the scene at Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge near Galveston. Photo by Michael Smith.

The risk of a problem incident can be worsened by a couple of things: First, residential growth in Texas is pushing neighborhoods into alligator habitat, making more people essentially intruders in alligators’ homes. Second, when people feed an alligator, it loses its fear of humans and sees them as a source of food. (Please do not feed alligators — it is dangerous and it is against the law).

The TPWD tries to strike a balance between coexisting with alligators and protecting public safety. There are high stakes for both humans and the alligator, as an offending alligator may be captured and relocated or euthanized.

TPWD encourages residents to reach out if an alligator’s behavior escalates to an emergency. The agency defines “emergency” as a situation “…in which an alligator has attacked a person or pet, or is in a public or private place (parking lots, roads, highway, play grounds, public beaches, etc.) creating a safety hazard,” according to the TPWD Nuisance Control Protocol for Alligators.

However, merely spotting an alligator does not make it a nuisance and does not constitute an emergency. Also “nuisance” alligator is defined by law as one that is killing livestock or pets, or is a threat to human health or safety.

Keeping these guidelines in mind, a person who needs to report a nuisance or emergency situation with an alligator should call the TPWD law enforcement communications center in Austin at 512-389-4848. Warner assured the group that he and his colleagues will respond to their concerns if an alligator becomes a nuisance. While he noted that the risk was low, he understood that “the consequences are enormous” if someone is harmed.

GATOR AID

Warner said that the American alligator “is a conservation success story.” The big reptiles were once hunted almost to extinction for their skins and meat. After getting legal protection, populations began to recover, and today they are doing well.

The demand for alligator products still exists, so TPWD grants permits to farms that raise alligators from eggs for the market. Additionally, the state allows seasonal hunting for those who apply for a special permit.

In Texas, most of the alligator population is found along the coast and in nearby wetlands. They follow the drainage systems of large rivers upstream, which is why they live in the Metroplex along the Trinity River. American alligators reach from six to 14 feet (occasionally longer), with males getting bigger than females, according to TPWD.

The American alligator eats almost anything it can catch, including fish, snakes, birds, turtles, and even smaller alligators. They actively hunt at night, so anything splashing around in the water at night is likely to attract the attention of a hungry alligator.

ALLIGATORS ON THE RISE?

A baby gator swims at Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge near Galveston. Photo by Michael Smith.

A baby gator swims at Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge near Galveston. Photo by Michael Smith.

At the meeting, the conversation returned several times to why Lake Worth residents were reporting more alligator sightings in the past couple of years.

Denkhaus pointed out the significance of bigger gators dining on smaller ones.

He said back in 2011, he and a graduate student were working with alligators.

“What struck us was that the vast majority of gators were from 6 up to 11 feet. We found virtually no little gators,” he said.

He asked residents if they remembered when a poacher killed an 11-footer near the Nature Center.

He reiterated that cannibalism by large alligators is one way that populations are controlled.

“Maybe the 11-footer had been taking care of lots of little gators,” he said.

With the big boss gone, more young alligators were likely reaching maturity. Those might be some of the ones the residents are seeing.

American alligators have 80 sharp teeth. Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge manager Rob Denkhaus said big alligators help keep the overall alligator population down. Photo by Michael Smith.

American alligators have 80 sharp teeth. Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge manager Rob Denkhaus said big alligators help keep the overall alligator population down. Photo by Michael Smith.

Denkhaus also addressed the misconception among some of those at the meeting that the Fort Worth Nature Center and Refuge was allowing people to bring alligators to the refuge and release them. Might that account for more gators? Denkhaus denied that such a practice was allowed.

He did share an observation that might explain why alligators may have shifted their habits.

“When was the last time the lake was at conservation levels?” asked Denkhaus.

Conservation level is “the amount of water an entity can impound at a reservoir under its Water Rights Permit” according to the Tarrant Regional Water District.

Denkhaus answered his own question: “June, 2019.”

Since that time, the water hasn’t stayed up for an extended period. Who knows how that may have affected the behavior of the alligators?

At the end of the meeting, Warner shared his contact information with the group. In addition, Denkhaus said the Nature Center may enlist a researcher who can add to the refuge’s knowledge about alligators in and around Lake Worth.

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter. Also check out our new podcast The Texas Green Report, available on your favorite podcast app.