The Southwestern Medical District Urban Streetscape Master Plan includes a new 25-to-30-foot-wide pedestrian bridge to connect the eastern portion of Harry Hines Boulevard and the O’Donnel Grove. Images courtesy of Texas Trees Foundation.

Jan. 25, 2017

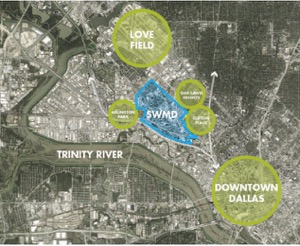

When the Texas Trees Foundation analyzed the Dallas urban tree canopy in 2015, it uncovered an area in dire need of green replenishment. Surprisingly, it wasn’t an industrial district, though trees are scant in many of those; nor was it a languishing neighborhood in impoverished corner of the city. No, the district suffering from a distinct lack of green byways and leafy cover was Dallas’ emerging jewel: The otherwise thriving Southwestern Medical District.

Situated just three miles northwest of downtown, the district encompasses three world-class, redesigned major hospitals: Parkland Health and Hospital System, Children’s Medical Center and UT-Southwestern Medical Center, which includes the UTSW campus and the sparkling new $800 million William P. Clements Jr. University Hospital. The new hospital strives to encourage efficiency and wellness with its modern layout, worldly art collection and generous city views. Similarly, the many related outpatient and training centers comprise that 1,000-acre district are highly evolved medically and architecturally.

All the new buildings have brought glassy towers, brisk valet services, refurbished lobbies and a towering orange Chihuly glass sculpture that brightens the look of the Seay Biomedical Building.

But the medical district’s growth has been uneven. Development of the natural surround, never a major factor in this once-industrial part of town, has lagged. The Texas Trees Foundation study found that the medical district has a tree canopy of just 7 percent, far short of the ideal 40 percent that the U.S. Forestry Service recommends to mitigate carbon pollution, cool urban concrete and envelop humans with a robust fauna.

But the medical district’s growth has been uneven. Development of the natural surround, never a major factor in this once-industrial part of town, has lagged. The Texas Trees Foundation study found that the medical district has a tree canopy of just 7 percent, far short of the ideal 40 percent that the U.S. Forestry Service recommends to mitigate carbon pollution, cool urban concrete and envelop humans with a robust fauna.

Dallas overall has a more sufficient tree canopy, 28 percent on average, but that is due in large part to the Great Trinity Forest that hugs downtown. Trees and shrubs still fall short in many places where they’re needed most, where people congregate and human activity buzzes, at Dallas schools and the highly trafficked medical district, said Janette Monear, chief executive officer of the Texas Trees Foundation.

And that is why the TTF study (actually a compilation of tree assessments done from 2010 to 2015) zeroed in on the Southwestern Medical District, because enhancing the natural environment there could have a huge impact.

Healing environment

Greening can be especially beneficial in a medical district, because it can improve human healing. Studies have shown that providing trees and grassy landscapes can help patients recuperate faster and even reduce the effects of ADHD, Monear explained.

In addition, tree respiration helps cleanse the air and offset smog pollution, an obvious benefit to all, but especially meaningful for those with reduced health or respiratory illnesses.

Trees also are urgently needed because this particular expanse of city, with its dense array of buildings and attendant concrete parking garages, is a major heat island. In the summer, it retains heat during the day and fails to cool off at night, leading to higher energy use and a more dangerous environment for people who’re sensitive. Trees, vegetation walls, rainfall gardens and turf easements are key ways to cool heat islands.

The TTF study led to a new extensive streetscape plan for the medical district - the Southwestern Medical District Urban Streetscape Master Plan - which calls for all of this and much more.

The TTF study led to a new extensive streetscape plan for the medical district - the Southwestern Medical District Urban Streetscape Master Plan - which calls for all of this and much more.

Improvements to the Medical/Market Center TRE Station Connection. Courtesy of Texas Trees Foundation.

Developed by Design Workshop Inc. for Texas Trees Foundation, the plan calls for hundreds of trees, safer and wider walkways, a retail district and an elevated park. It’s all about greening, but also more broadly about making the area fully habitable, in recognition of the 100,000 people who visit doctors there every year, the 30,000 employees of the sprawling district and the 12,000-plus urban dwellers in adjacent, nascent neighborhoods.

Trees were the seeds of the project. The foundation obviously prizes trees, which shade, cool and absorb carbon dioxide and the plan for the medical district offers ambitious arboreal goals:

• Shade at least 80 percent of the hardscape using mainly large growth canopy trees.

• Put a minimum of 50 percent of the parking spaces under shade trees.

• Prioritize native trees with long lifespans and don’t box them in with excessive hardscape. (Monear calls those inadequate boxes of soil that developers sometimes set aside for planting trees within vast deserts of concrete “tree coffins” because it shortens the trees’ lifespans.)

• Use a wide variety of hardy trees, such as cedar elms, burr oaks, magnolias, desert willows, plums, red buds, Texas hickory and Chinese pistache, to name a few on the recommended list.

• Use materials to make hardscapes more reflective, assisting the trees in mitigating the heat island effect. (A well-treed area can be 10 degrees cooler than surrounding open urban areas. Tree groves can be even cooler.)

But as foundation staff began collaborating with executives and staff at the SW Medical District, a much larger vision for a comprehensive streetscape evolved.

The big green picture

After surveying more than 600 employees, the Texas Trees Foundation realized that people working at the hospitals wanted not just trees, but more and safer walkways (with regard to traffic and crime), green useable spaces for themselves and patients, and better connections to transit. They reported that they had no way to walk to restaurants, not to mention, very few restaurants.

Monear believes the 139-page plan, unveiled this fall, is the most extensive urban improvement plan to hit Dallas in recent memory.

“One of the things about this project, there’s no medical district that’s done this kind of comprehensive plan. It’s going to bring continuity to the district; it’s going to bring mobility to the district, and it’s going to bring economic development to the district. It will spur economic development,” she said.

Monear believes the 139-page plan, unveiled this fall, is the most extensive urban improvement plan to hit Dallas in recent memory.

In addition to the envisioned bike paths, greener transit stops, exercise stations and pathways, the plan sketches out a way to get people across the pedestrian-repelling Inwood Road and Harry Hines Boulevard intersection that marks the approximate center of the Southwestern Medical District. Instead of carving up the district, the cloverleaf at Harry Hines and Inwood would become the “Green Heart” of the project (with Harry Hines being “the spine”), according to the master plan.

In addition to the envisioned bike paths, greener transit stops, exercise stations and pathways, the plan sketches out a way to get people across the pedestrian-repelling Inwood Road and Harry Hines Boulevard intersection that marks the approximate center of the Southwestern Medical District. Instead of carving up the district, the cloverleaf at Harry Hines and Inwood would become the “Green Heart” of the project (with Harry Hines being “the spine”), according to the master plan.

Phase one of the Green Heart project improves pedestrian connection across the cloverleaf intersection at Harry Hines and Inwood Road, with the addition of a new overhead pedestrian bridge. The new 25 to 30-foot-wide pedestrian bridge will connect the eastern portion of Harry Hines Boulevard and the O’Donnell Grove, pictured below. Courtesy of Texas Trees Foundation.

The elevated park proposed for the cloverleaf would be similar to Klyde Warren Park, the green roof that Dallas philanthropists recently plopped over the top of Woodall Rogers Freeway instantly connecting Uptown to downtown and creating a green gathering spot for downtown residents.

The elevated park proposed for the cloverleaf would be similar to Klyde Warren Park, the green roof that Dallas philanthropists recently plopped over the top of Woodall Rogers Freeway instantly connecting Uptown to downtown and creating a green gathering spot for downtown residents.

The “sculptural land bridge” that would hover over Inwood and Harry Hines is envisioned to contain parks, walkways, dog runs, a bird sanctuary, a rain garden forest, kiosks.

It’s a vision that’s both dreamy and practical. The extensive “green infrastructure” would draw in people to a park that would be a singular destination, while at the same time managing storm water with its rich overlay of native plants and turfs that slow runoff.

Green intervention

It’s really no wonder, and no one’s fault, that the Southwestern Medical District would need a green overhaul. Having developed over more than 100 years, the medical district, upon examination, feels like anything but a cohesive community, its buildings spilling in every direction, some penned in by garages or roadways, others jammed against each other obscuring signage and making for confusing first visits.

The Clements hospital stands apart, a well-appointed architectural marvel, but it is difficult to access on foot for medical students or staff working in the legacy hospitals a good distance away. Some elevated walkways have been installed, but these are first steps.

Only a little more than half of the district’s 21 miles of streets even have sidewalks, and many of those are not wide enough to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, according to the streetscape plan. Furthermore, about half of the existing sidewalks lack surrounding soil and trees.

In addition, the area lacks formal bike paths, so far missing an opportunity to connect bicyclists to the nearby Turtle Creek, Trinity Strand and Katy trails as well as to DART and TRE transit stations within the district. The streetscape plan shows how nearly 3 miles of bike trails can be incorporated.

In short, the plan details both the diagnosis - that this area needs a green intervention and a master roadmap – and the prescription for long-term wellness.

But the cure won’t be cheap. Each phase of development suggested by the master plan will cost $1 to $30 million and how quickly the needed cash can be found remains to be seen, though in each case, the city, state and private partners share an interest in the improvements. (All told, the total improvements could top $70 million and that’s not factoring in the full rooftop for the “Green Heart.”)

No one expects the vision to develop in a snap, but Monear says the plan will take first steps in 2017, aiming to plant trees by the fall.

All told, the total improvements could top $70 million and that’s not factoring in the full rooftop for the “Green Heart.”

The Texas Trees Foundation has put in a request for $16 million in bond money from the city of Dallas, arguing the multiple benefits of the project. The nonprofit also is pursuing money from the Texas Department of Transportation and the North Central Texas Council of Governments, she said.

Private donors and investors will be needed as well and Monear says she is already hearing from some.

“They’re already grabbing onto it. We’re already getting calls from builders and developers; investors looking at land.”

The city of Dallas also already has enticements in place in the form of two Tax Incentive Funding Districts for eligible improvements in the medical district.

As importantly, everyone seems to be on a page that green, stress-relieving infrastructure and concurrent economic redevelopment is needed.

“The best thing about it is that the hospitals are 100 percent behind this, they’re very excited about it and they are our partners,” Monear said.

Breaking down the phases

The first phase aims to improve the streetscapes along the “spine” of the district, focusing on Harry Hines, which bisects the area. This would be high impact and serve to connect multiple elements, tying in the developing residential area on the other side of the boulevard from the hospitals. This phase would make the district immediately more walkable, which could prompt more workers and visitors to leave their cars at home and travel to the area by DART trains or even via the TRE, compounding the environmental benefits.

This initial parry, called Green Spine Phase 1, would cost between $26-$30 million, according to the plan.

(Green Spine Phase 2, which calls for bilevel traffic on Harry Hines and even more pedestrian features could come later. Similarly, the “Green Heart” project could be built in phases, starting with a relatively modest Phase 1 that would build a pedestrian bridge and rain gardens at an estimated cost of $8-$12 million.)

The hospital and district leaders are eager to see the district become more walkable and integrated, said Ruben Esquivel, vice president for community and corporate relations for the Southwestern Medical District.

“For us it is important because we are committed to a healthy population,” he said. “Anything we can do to improve health is totally aligned with our mission.”

An improved district also will help recruiting as UT Southwestern scans the world to keep its rosters filled with top doctors and professionals. People evaluate the work environment and their ability to live nearby, Esquivel said, noting that residential areas are rapidly developing around the district.

New signage, which will help delineate where the district begins and ends, as well as improving “way finding,” is underway already and being installed in early 2017, Esquivel says.

The full streetscape plan will be phased in over many years, he says, but the hospitals are happy to partner with the Texas Trees Foundation and rely on their expertise in choosing the right trees and employing nature to improve human lives.

“You have to understand the trees, how they grow, how much CO2 they can sequester, which are better at shading . . . and how you have a balanced tree canopy so you don’t lose all your trees in the event of a disease,” Monear says, explaining that the foundation is optimistic, seeing the city and medical district embrace the greening opportunity.

“We’re getting a great response (to the plan.) A lot of people like what we’re doing,” she said.

RELATED STORIES

Texas Trees Foundation reveals state of Dallas urban forest

Stay up to date on everything green in North Texas, including the latest news and events! Sign up for the weekly Green Source DFW Newsletter! Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.